From Prisoner to Patriarch: A New Orleans Love Story

Retired tailor Nunzio Giovanni “John” DiStefano is one of many Italian immigrants who moved to the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries in pursuit of the American Dream. But DiStefano’s story is no ordinary immigrant’s tale. Unlike most New Orleans area residents with Sicilian heritage, he came to New Orleans involuntarily, as a prisoner-of-war in World War Two. Along with about 1000 of his countrymen, DiStefano, now a spry and energetic 90-something, spent 1944 and 1945 as a captive at Jackson Barracks. During that time, he met his future wife. Vergie Battaglia was the daughter of Sicilian immigrants and one of seven sisters, four of whom would go on to marry Italian POWs and bring them back to New Orleans to settle down and raise their families.

Early Life

Born in 1923, Giovanni DiStefano grew up in an Italian enclave in Tunisia, which was a French North African colony in the early 1900s. He was the ninth child—five others had died before he was born. His father died in an accident when DiStefano was three and his younger brother Antonio (“Tony”) was only 18 months old. To support the family, his mother washed clothes for others. “I don’t know how she managed to put food on the table, but somehow she did,” DiStefano says in perfect English with a lyrical Italian accent. His mother died in 1940, “too poor for any medication.” In March 1943 he and Tony signed up for the Army.

Captured in Tunisia

By the Spring of 1943, World War II was raging, and things were not going well for the Axis powers in North Africa, especially for the Italian forces. Mussolini had left them severely underequipped, with little food or ammunition. DiStefano recalls that a British soldier stopped a truck of 40 Italian soldiers, one of whom could speak English. The Italians were so desperate for food, they put down their guns and ammunition without a fight. “One man disarmed us,” DiStefano says. There were some Germans in the group as well, but the British quickly separated them from the Italians. “We didn’t get along and didn’t understand each other,” according to DiStefano.

The British were overwhelmed with POWs at the end of the battle in Tunisia, and the US agreed to take custody of about 51,000 Italian prisoners, first to temporary camps in Algeria, where food and necessities were in short supply. “There was the desert, they had no water, one fountain for everybody at the camp and very little food because the German submarines in the Atlantic were sinking so many ships,” DiStefano recalls. “And lice, body lice. Unbelievable. We had to shake the blankets out every morning.”

An American major came to the camp one day, and someone told DiStefano the major spoke French. “So, I told him—in French—that my brother and I were born and raised in North Africa, but we’ve never seen anything like this. We’ll do anything, anything at all just to get out of this camp. We can’t take the heat, no water, no food.” The major told him the Americans planned to take 400 men from the camp and send them to the United States. “He said the magic words!” DiStefano ran to tell his friends, but some of them were afraid to cross the ocean in a boat that might be sunk by the Germans. “I don’t care,” DiStefano remembers telling them. “I’d rather die quickly than a little bit at a time over here.” When the day came that they asked for volunteers, DiStefano was the first in line, along with his younger brother. He was 19, his brother 17, one of the youngest prisoners in the group. “He had to lie to get into the Italian Army, because he wanted to stay with me. Throughout the whole thing, we were together.”

Discovering America

After a long trip across the Atlantic, the prisoners landed in Newport News, Virginia. DiStefano recalls, “for months, we didn’t know what it was to have a shower. When we got off the ship in the US, they took the big group of us into showers. We didn’t want to get out! The MPs had to pull us out.”

The last time the men had traveled by train it was a freight car, made for “four horses or 40 men,” so they were pleasantly surprised when they were loaded into a Pullman passenger train, complete with sleeping cars. “There was a guy who fixed up our beds and everything,” DiStefano says. They were given very little food, however, because the men had been so malnourished for so long. “They had to start very slowly with us. A few soldiers ate too much and got sick,” he says. “But there were white plates in the mess hall. We got to shower any time we wanted to. We finally discovered America.”

DiStefano’s company was initially taken to Nebraska, where they spent nine months working on potato and sugar beet farms. They were paid $3/month. After Italy surrendered in September 1943, he recalls, they got new uniforms without the “PW” on the back of their jackets for “Prisoner of War,” since Italy joined the Allies and was no longer an enemy combatant. “We could go anyplace we wanted. They trusted us 100%,” he says. In March 1944 most of the Italian POWs being held in the US had signed a loyalty oath and were put to work in “Italian Service Units,” providing much-needed labor at a time of critical workforce shortages. They were issued new uniforms with a green oval “ITALY” patch on the sleeve.

When they weren’t working, the POWs passed the time playing cards, reading books (in Italian and French), and listening to the radio. “When we were in Nebraska, one of my friends received a little radio from his aunt in Cleveland,” DiStefano remembers. With a natural ear for languages, he used music to teach himself English. “Naturally, they had the most beautiful songs in those days, beautiful love songs. Perry Como, Frank Sinatra. I used to listen to the songs and memorize them. And I didn’t know what they meant. They had the Hit Parade every month, a little magazine, and I tried, from memory, to see if I could find some phrases. I would try to write them down by copying them from the magazine, so I could say a few words. I was good with the pronunciation—the first time I heard the English language I fell in love with it.”

Jackson Barracks

After being transferred to Watertown, NY, then to Syracuse, the prisoners found out they were to be moved once again, in the Summer of 1944. “When we found out the whole company was going to New Orleans, Louisiana, I said to myself, ‘New Orleans? There’ll be a few French people over there. I’ll be all right. I’ll be able to make friends right away.’”

“We arrived in Chalmette on the train, and they greeted us with music from American soldiers at Jackson Barracks—a little band,” DiStefano recalls. “We marched right over (the train was very close). Our whole company—the 41st company of about 1000 soldiers—arrived over the next few days.”

As the POWs got settled in at Jackson Barracks, they quickly took over the food situation. Among the prisoners was a chef who had owned a restaurant in Italy before the war. “Instead of the regular military food, he would prepare a meal for us, for the whole company,” DiStefano recalls. “And we had a table reserved for the American soldiers, or people that we would meet. Ten people could be invited every night to eat with us. Special people.” The soldiers would ask them what ingredients they needed and provide them. “We couldn’t believe it,” DiStefano said. “We were where we didn’t even have any bread, and now we were having a huge Thanksgiving dinner as prisoners of war. So naturally, to us the Americans were people sent by God.”

DiStefano worked at the New Orleans Port of Embarkation, loading supplies for soldiers in Europe onto cargo ships. The POWs were allowed to move around freely, as long as they checked out and back into the Barracks at night. They were transported back and forth on regular Army trucks.

Aside from work, the POWs were also allowed out for Mass and to visit the homes of local families. The Barracks would also host dances, and the young French Quarter Sicilian women were only too happy to attend and meet some new dance partners, with so many of the local men off at war. Local businesses sponsored the dances, and the Army came to fetch the women in trucks. When a friend said he was interested in a girl who was one of the seven Battaglia sisters, DiStefano came along to the dance. “I figured there would be at least one for me!” He was right.

One Sunday DiStefano and his friends devised a plan to visit the Battaglia family home. “I had a needle and thread with me, being a tailor,” DiStefano remembers. He took the ITALY patches off their uniforms with the intention of sewing them back on in the morning. They bribed one of the soldiers at the Barracks with cigarettes to raise the fence so they could get out. “We were waiting for the bus and a car stopped and said, ‘hey soldier, where are you going?’ We said, ‘Esplanade’ and they said, ‘come on.’ They thought we were American soldiers. They asked where we were from and we said ‘Puerto Rico, that’s why we don’t speak too good.’ I had it all planned.”

They found the house, thanked the driver and knocked on the door, where three of the Battaglia sisters were at home—but without their parents. “We told them we got a special permit to leave,” DiStefano laughs at the white lie. “We said we weren’t going to stay because their mother wasn’t there, but they said she’d be back soon, so we stayed. And that’s the first time I met my wife. I was 20 and she was a year older than me. We started talking and that was it.”

When he first met Vergie, she knew a little Sicilian, which is close to Italian, and he tried to speak as much English as he could. Much of the time they communicated through Vergie’s mother. “I was over her house and tried to say something in English, and she tried to say something in Sicilian. She said, ‘if you think you’re so smart, why can’t you talk English as good as I can talk Sicilian?’ I got the translation from her mother and I said, ‘you’ve got me there.’”

He recalls that his future mother-in-law was very nice and cooked Sunday dinners for the men. “A nice Italian dinner: pasta, red gravy, fried chicken, salad. She was smart—she knew she could get to the guys through their stomachs.”

The war was over by the fall of 1945, but it took a few months for the US government to arrange for the POWs’ repatriation to Italy, per the terms of the Geneva Convention. After 18 months in New Orleans, “one week before Christmas, they shipped us back to Italy.” From Chalmette they took a train to Newport News, then traveled 21 days on a boat to Italy, fearful of mines the whole way after one of the ships in their convoy blew up.

Vergie had relatives in Palermo, and two of her sisters got married to Jackson Barracks POWs there, but she was afraid to cross the ocean. DiStefano went to Palermo and stayed for a year, repeatedly visiting the American consulate to find a way to get permission to travel back to the US. He prayed to Saint Rosalie, the patron saint of Palermo, and Vergie would write every day. “They were impressed—I was pretty good with my English,” DiStefano says. He was in a tough spot, though, since he’d been born and brought up in Tunisia. “The French wouldn’t let me back into Tunisia, and the Italians said I wasn’t Italian.” Eventually, he found a sympathetic ear in the US Vice Consul who told him, “you’re going to have a country of your own as soon as you step into the United States.”

After working what he calls a “miracle,” DiStefano obtained an Italian passport and passage to the US on a merchant ship. He arrived just in time for Vergie’s birthday, January 10, 1947, and they were married on February 5 at St. Mary’s Italian Church, 1116 Chartres Street in New Orleans.

Return to the United States

Three years after they married, DiStefano became a US citizen. “The judge was surprised at my English and asked me where I learned. I said, ‘here is my teacher next to me,” and I pointed to my wife. The judge said, ‘well, young lady, you’ve done a beautiful job.’”

The DiStefanos first lived in the French Quarter, off Esplanade. He worked as a tailor and executive foreman for Haspel Brothers, and Vergie was a gifted artist, hand-tinting black-and-white photographs. They had three children, Ronnie, Maria, and Dino. DiStefano rose through the ranks at his company and eventually was running its plant in Tylertown, Mississippi, where the family lived for 10 years before he asked to be transferred back to New Orleans.

DiStefano still lives in the Lake Villa house he and his wife built in the late 1950s. The house was built high and strong, and survived the floods following Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Vergie passed away in 1976 and DiStefano remarried, but outlived his second wife Blanche as well. His 11 grandchildren and 15 great grandchildren visit him often and cherish his memories of a unique and fascinating Italian American journey.

Giovanni and Vergie DiStefano on their wedding day in New Orleans.

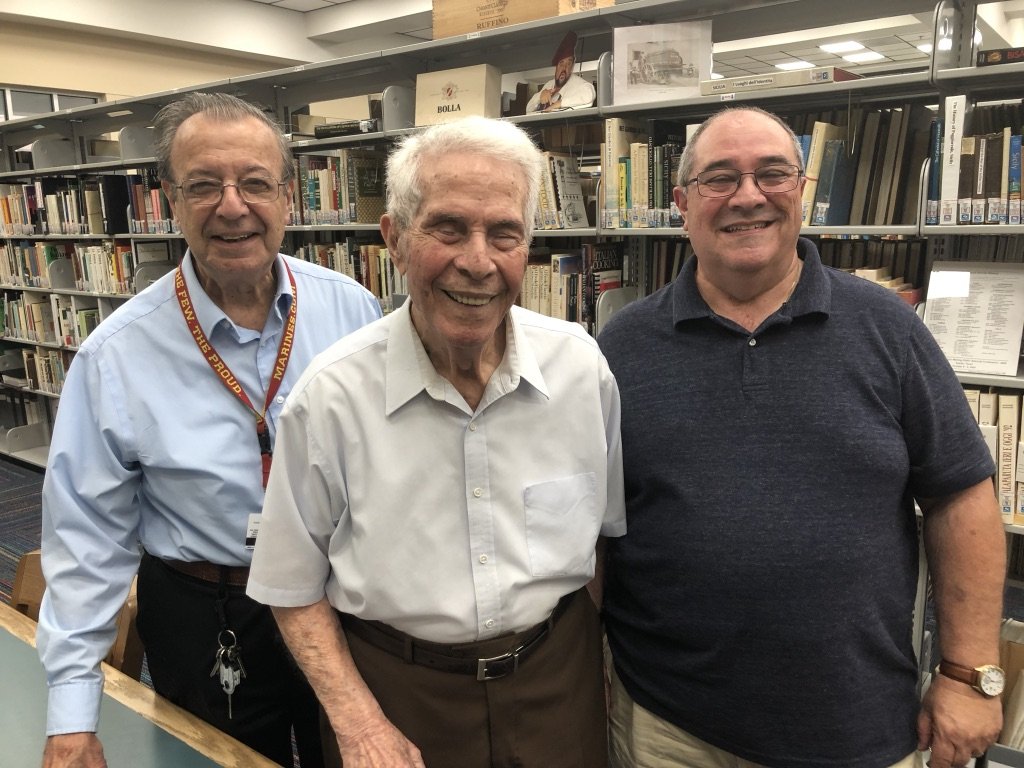

Giovanni “John” DiStefano with his son Ron, right, and American Italian Research Library Curator Sal Serio, left, in 2019